Updated 25/09/25

A number of strange strategic decisions were made in the second world war, which later in the battle led to an unnecessary amount of additional casualties and a huge loss of material. Now it is the case that in the heat of the battle a wrong decision can be made, but the decisions described below were deliberate and were taken from behind the desk. Here are some of these strange decisions. The first article is about the escape of the Allied army already at the beginning of the war, when the Germans had just invented and put into practice the Blitzkrieg.

Operation Dynamo

In the spring of 1940, more than two hundred thousand strong British expeditionary army was located on the European mainland. This army had to be able to help the allies France and Belgium as soon as necessary. When the Germans invaded France and Belgium in May 1940, that aid was very welcome. The British resisted, but because of the rapid advance of the Nazis, people were pushed back. From a German perspective, Fall Gelb, the code name for the attack on France, was a huge success. French border positions were overrun in fast-train travel and the British expeditionary army was surrounded by Dunkirk, the only remaining Allied port. The fact that the British army, together with a French force, managed to escape, was partly due to the much-discussed Halt-Befehl“Halt-Befehl” of Hitler.

On May 24, 1940, Hitler ordered his troops who advanced to the Channel to stop at Grevelingen, a city a few kilometers southwest of Dunkirk. From a German perspective, that was a dramatic decision afterwards. The Nazis lost the initiative and enabled the British to set up and implement an evacuation plan. The British and French who were rescued were later part of the base of the fall of Nazi Germany.

The decision to temporarily cease the advance and not to take Dunkirk did not fall from the sky. Göring had previously assured Hitler that thanks to his Luftwaffe it was impossible for the British to escape. It also seemed extremely unlikely that the thousands of Britons could get away from Dunkirk. It was not for nothing that it was later spoken of “The Miracle of Dunkirk”. The Luftwaffe had to be used for the destruction of the surrounded British and French units. Deployment of loss of tanks was thus prevented. However, Hitler was found to overestimate the destructive force of the aerial bombing.

In recent decades, historians have discussed the question of why Hitler issued the Halt-Befehl. According to some lectures, the German leader wanted to vote the British more favorably, so that, after the final fall of France, peace could be negotiated more quickly. However, this seems unlikely. It is more obvious that Hitler, like other military leaders, was worried about the speed with which the attack on France proceeded. The southern flank became vulnerable and in the previous weeks the Blitzkrieg had asked for many of men and equipment. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt had already ordered the advance a day before the issue of the Halt-Befehl for similar reasons to temporarily cease the advance. This after he learned that a strong French defensive unit had been set up at Grevelingen. Due to the intensive use during the Blitzkrieg, according to the field marshal, many divisions had become vulnerable, due to fatigue, but also due to fuel shortages. Von Rundstedt did explicitly distance himself from the Halt-Befehl after the war and fully submitted the responsibility for the decision to Hitler. Whatever the exact reason for the Halt-Befehl, the fact is that the British took advantage of this first battle break after fourteen days of continuous German attacks. The defensive line at Dunkirk was strengthened and a large evacuation campaign was launched. This campaign became known as Operation Dynamo, as the plans were made in the dynamo chamber of the naval headquarters under the castle in Dover. Churchill wanted to prevent the Germans from getting the impression that there was a possibility to negotiate with the British.

On May 26, 1940, Winston Churchill commissioned the evacuation of the force at Dunkirk. For the rescue operation, all available boats had to be deployed. The fact that the port of Dunkirk was severely damaged by long bombardments of the Luftwaffe made the evacuation even more difficult than it already was. To a large extent, embarkation also had to take place from the beaches. For this purpose, especially the smaller ships with a smaller draught were suitable. Exactly how many boats carry out to save the British expeditionary army is not entirely clear, partly because many boats also participated voluntarily and were never officially registered. In general, it is kept on about 900 participating ships. The record number of troops rescued with one ship came in the name of the RMS Tynwald. This passenger ship traveled to Dunkirk five times and evacuated a total of around 9,000 British and French. It is estimated that during the operation about seventy vessels were lost. In his memoirs, Churchill wrote that at most 45,000 troops were thought to be saved beforehand. Later, that expectation was slightly revised upwards, but the eventual success of the operation exceeded all expectations. During Operation Dynamo, a total of about 338,000 men were picked up safely and transported to England, so that they could continue to fight against the Nazis. The British had been defeated on the European mainland, but not destroyed. Hitler’s decision to issue the Halt-Befehl had major consequences for the Germans on June 6, 1944, D-Day. Of course, the troops rescued at Operation Dynamo were put ashore again in Normandy on D-Day. The question is whether D-Day had been so successful without this force of nearly 340,000 troops.

Exercise Tiger

On April 27 and 28, 1944, a major tragedy unfolded at Slapton Sands on the coast of Devon that would kill a large number of American soldiers.

The operation was intended as training for the landing at Utah Beach in Normandy. 3000 Residents of the area around Slapton Sands were evacuated to be able to perform the exercise as real as possible. Slapton Sands and the surrounding area was very similar to that part of the French coast, later referred to as Utah Beach and part of the landing area of part of Normandy, where the largest invasion of the war would take place.

Exercise Tiger was designed to mimic the landing as realistically as possible. Large quantities of landing craft full of soldiers, tanks and equipment were deployed. On the first day of the exercise, things went pretty wrong. H-hour was set at 7:30 a.m., but because a number of landing craft had been delayed, H-hour was moved to 8.30pm. Some of the landing craft never received this message and thus landed an hour early on the beach. During the resulting chaos, too early shots were fired from all sides, causing unnecessary deaths for many American soldiers.

On the second day, a number of warships had to guard the mouth of Lyme Bay, but one of the ships, HMS Scimitar had a collision with a landing craft and had to withdraw. Only the Azalea remained to protect the bay. In addition, due to an error by the LST’s communications room, a wrong radio frequency was transmitted to the landing craft, so that the message about the presence of enemy ships in the Channel was not received. Under cover of darkness and due to the lack of adequate protection, a number of German Schnell boats (fast torpedo boat of the German Kriegsmarine) managed to sneak in to Lyme Bay. Two landing craft were sunk and a third was severely damaged. More than 700 Americans lost their lives. Lack of training on the use of life jackets, heavy packing, lack of communication and the freezing water contributed to the disaster.

Still, thanks to training at Slapton, fewer soldiers died in the actual landing at Utah Beach in Normandy. The disastrous training was therefore not entirely for nothing.

Because there was a fear of the influence on the morale of the troops, the large number of victims of the exercise was kept quiet until long after the war.

Operation Cobra

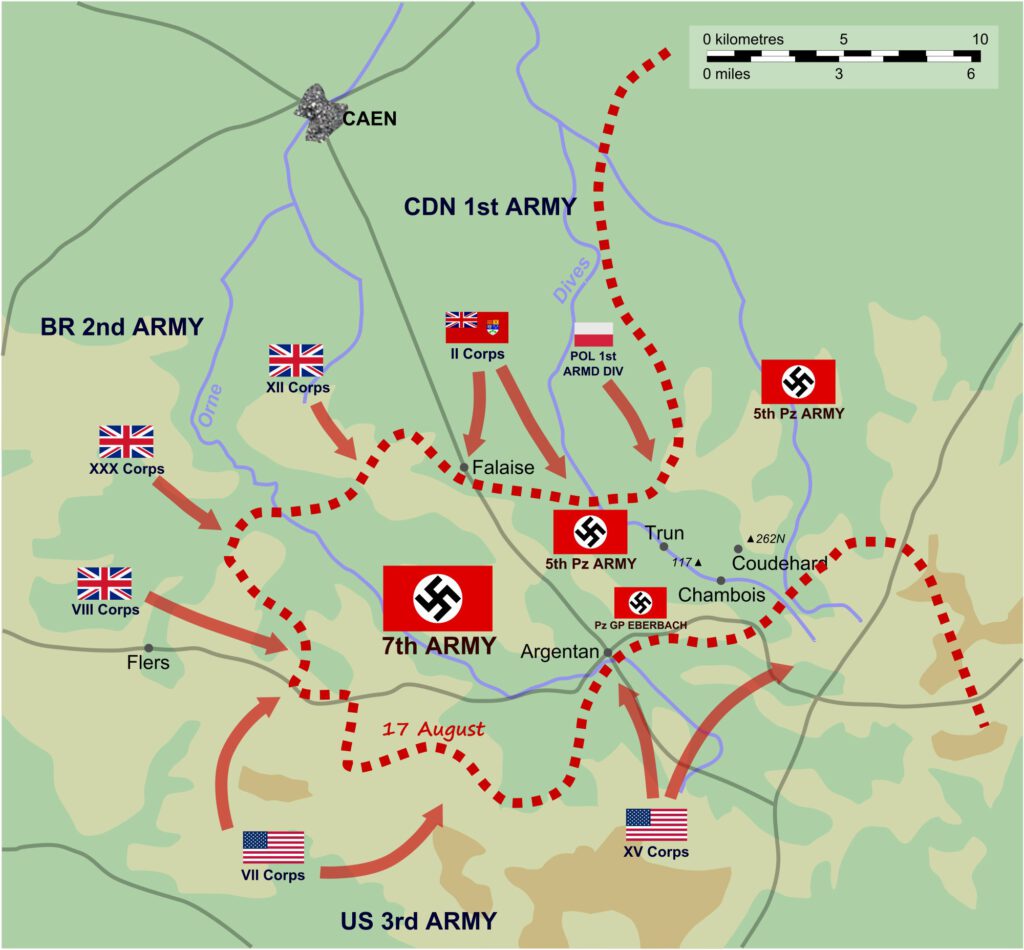

After the successful landing in Normandy, the further advance of the Allies proved to be very difficult. It was only after the Allied outbreak in Operation Cobra that movement came into the front. Hitler’s order that the German troops should not withdraw caused the American units broken out at Operation Cobra under Patton on their southern flank to encounter almost no opposition. Meanwhile, Montgomery began an attack with Operation Totalize against the German units at Caen. This put forward two British armoured divisions far enough to become threatening to the German line. Due to the combination of both attacks, 28 German infantry divisions and 11 armoured divisions were at risk of being taken into an Allied tang movement. After the breakdown of Operation Lüttich (a German counter-attack against the outbreak of the Allied forces from their Norman bridgehead), the German 5th Pantzercorps was ordered to attack in a southwesterly direction, although it risked being locked in between Falaise and Argentan by Allied forces.

The inclusion

On July 24, despite the bad weather, Allied aircraft began to bomb and shell the target area. As a result, the Allies accidentally killed about 150 victims of their own. Operation Cobra finally started the next morning with more than 3,000 aircraft. Friendly fire remained a problem, as the attacks caused another 600 victims of their own, including Lieutenant General Lesley McNair. On 8 August, Patton’s 5th Armoured Division reached Le Mans, which joined the French 2nd Armoured Division under Leclerc. Bradley and Montgomery agreed on the same day to try to contain the German army west of the Seine. Patton’s two armoured divisions would join Montgomery’s divisions, which would rotate parallelly from Caen in a southwesterly direction and then move north from Le Mans. Patton’s 15th Corps now swerved 90 degrees to Argentan, while his other divisions moved to the Seine. This allowed Bradley to set up both a short and a long plier movement. The long tang movement was intended for the German troops who escaped from Falaise.

On August 16, Hitler’s German troops received orders for a return in three phases: first a retreat of all German troops west of the Orne, following a retreat over the Dives and finally crossing the Seine. The 2nd SS-Pantzer Corps had to keep the area east of Falaise to allow the exit from Falaise. This command came too late because crossing three rivers under artillery shelling was not an option and because due to the Allied air superiority there were no major German troop movements possible during the day. Bradley ordered Patton’s 15th corps to stop north of Argentan. As a result, a strip of 25 kilometers wide remained open, allowing German troops to try to escape. Patton was furious about this decision by Bradley and felt that the encirclement should be completed. Particularly parts of the 12th SS-pantzer division and the Canadian 1st Army provided bitter fighting over several days. During these battles, the Polish 1st Armoured Division, led by Stanislaw Majzek, closed the encirclement to prevent the flight of the German troops. But also the hardened and experienced Poles could not prevent a number of SS units from breaking out, which suffered large losses because they were shot at by the Poles who held the higher area.

More than 5000 Germans, including a division commander, were captured by the Poles. Between August 18 and August 21, the terrain for the surrounded German army slumped to an 8 km wide strip. Every day it was shot with 80,000 grenades and air strikes (Corridor of death) were constantly occurring. Although nearly 100,000 Germans escaped from the pocket before it was definitively closed on August 22, about 50,000 were captured and 10,000 killed. In addition, 344 tanks and armoured vehicles, 2447 trucks/vehicles and 252 artillery pieces were captured or destroyed. Had Patton gotten his way, the number of Germans locked in the pocket would have been considerably more. The 100,000 escaped Germans have of course encountered the Allies again in the further course of the war. After they won the Battle of Normandy, the Allied troops moved free to the River Seine and reached it on August 25. Operation Overlord finished on September 1. The German 7th Army was practically destroyed.

Pointe du Hoc

General Eisenhower had designated Pointe du Hoc as Target number one when landing at Omaha beach. Erwin Rommel, the commander of the Antlantikwal, had, as propaganda, extensively photographed at the defense complex of Pointe du Hoc, an excellent rocky point between Omaha beach and Utah beach. Rommel would have challenged Eisenhower to designate Pointe du Hoc as Target number one. Conquering Pointe du Hoc and destroying the cannons was assigned to the US 2nd Ranger battalion. A very dangerous job because to conquer Pointe du Hoc they had to climb a steep wall, while the Germans from above tried to shoot down again. The Rangers practiced a lot prior to the mission on several steep rocks along the English coast and the Isle of Wight.

A group of Rangers from the US 2nd Ranger battalion was assigned this task, while the remaining Rangers had to fight with the US 5th Ranger battalion on the landing on Omaha beach, along with the 1st and 29th Infantery division and pushed on to Pointe du Hoc. Once this had succeeded, the Rangers had to advance to Isigny-sur-Mer, taking the traffic junction to stop the advancing Germans from the interior. Through the qualification Target number one, conquering Pointe du Hoc became a prestige matter for the U.S. military.

The commander of the Rangers, James Rudder, was not supposed to lead the attack himself. That role was assigned to Major Cleveland Lytle. This major had a lot of criticism of the plan and felt that the Rangers were going to attack the wrong place. The Rangers, according to Lytle, were better able to worry about the battery at Maisy (La Martiniere/WN84 and Les Perruques/WN83 and Ferme Foucher), from which both Utah beach and Omaha beach could be bombed. Lytle was fired by Rudder because of this criticism, supposedly because he was not fit to carry out the attack. However, it seemed more like Rudder did not want to stay behind in England and therefore chose to carry out the operation itself. In retrospect, Lytle’s opinion turned out to be perfectly correct and Rudder’s opinion turned out to be incorrect.

Cleveland Lytle was strangely not put on inactive by the military leadership or anything like that. On the contrary Lytle was given command of the 90th Infantery division HQ and later of the HQ 1st battalion on 2 August 1944. Lytle was rewarded with the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star with 2 leaf oak clusters, the Bronze Star, the Purple Heart with 3 clusters and received the Order of Leopold from Belgium. Lytle was a courageous and valued member of the U.S. military and has never suffered from his conflict with Rudder.

During a two-man patrol on the conquered platform, Len Lomell found a few wooden poles instead of cannons and did not spend any more time on it. After some searching in the fields behind the platform, Lomell with his mate Jack Kuhn found a number of cannons with the accompanying ammunition. Slightly camouflaged, but not a German nearby. By Lomell and Kuhn, with the help of Frank Rupinski and his men from Company E, the cannons with grenades were defused and the ammunition inflated.

After the Rangers had conquered Pointe du Hoc and no cannons were found on the plateau, Rudder decided to defend the road behind the rock and not to advance to the crossroads at Isigny-sur Mer and further to the battery of Maisy. Because of this decision by Rudder, who also cost a lot of casualties due to the constant skirmishes with the Germans, the cannons of Maisy could continue to fire on Omaha and Utah beach until 3 days after D-Day. The Maisy Battery was eventually knocked out under Major Richard Sullivan’s leadership by the A, C and F companies of the 5th Ranger battalion. The capture of the Maisy Battery cost another 18 dead and wounded U.S. elite troops. Rudder’s 2nd Ranger battalion did not play any role in this conquest. According to Rudder, his men were unable to contribute to the fighting.

In retrospect, it appeared that the French resistance had already reported that no cannons were lined up at Pointe du Hoc. In other words, the U.S. Army leadership already knew about this. The attack on the rock of the Rangers was therefore completely unnecessary as Lytle had already predicted. Eisenhower had wrongly designated Pointe du Hoc as Target number one. It remains that the storming of Pointe du Hoc can be qualified by the Rangers as a heroic act.

To cover all this up, the Maisy Battery was completely buried under a heap of sand, until the battery was discovered in 2004 by an English amateur historian Gary Sterne and excavated in 2006 and the following years. The initial number of victims of the operation amounted to 135 deaths and injuries of the 225 troops who had landed. Because of the unexplained behavior of Rudder, many dead and wounded were added. The number of victims on Utah and Omaha beach specifically caused by the Maisy Battery is unknown.

Source:

The D-Day cover up at Pointe du Hoc, Gary Sterne

Traces of War – Peter Kimenai

Wikipedia

The Battle of the Scheldt

After the battle of Falaise, the Allies were able to make a rapid advance to the north almost unhindered. It was soon clear that the supply from the Normandy coast was going to pose a problem. That is why conquering Antwerp, with its port, was a major priority. If the supply could take place from Antwerp, it saved a huge amount of time and there was no longer a permanent return to and from the front between Normandy and the front (Red Ball Express). After all, Antwerp was a lot closer. In the evening of 3 September 1944, the XXXth British Army Corps, under the command of Brian Horrocks with its 600 tanks, reached Brussels, after covering 300 kilometers in 8 days. Antwerp actually fell without a fight on 4 September. Due to the rapid surprise by the 11th British armoured division (Black Bulls), led by Major General Pip Roberts, the port installations remained almost completely undamaged. The German commander, Major General Christoph Graf zu Stolberg-Stolberg, surrendered at the end of the afternoon. The German prisoners of war were housed in the empty cages of the Antwerp zoo. Grand Admiral Dönitz found the surrender of Antwerp cowardly and hastened. According to him, the army had been negligent to sound the alarm in time and destroy the port installations. In reality, Dönitz’s Navy lacked enough explosives to destroy the bulky port installations.

The Allied armies were major consumers of ammunition, fuel and food. By the end of August, 2,000,000 troops and 500,000 vehicles had already been landed in Normandy. Each division needed 400 to 650 tonnes of supplies per day, totaling 25,000 tonnes. Forecasts indicated that the need would rise to 40,000 tonnes per day. In addition, the food supply in the liberated part of France required a further 2500 tonnes of food per day. Antwerp was therefore the solution to the supply problems of the Allies. However, Antwerp is 75 kilometers upstream from the Scheldemonding. The German coastal batteries blocked the passage for the Allied convoys. In order to allow for free passage, the two banks had to be purified of German troops and the water had to be made mine-free.

It was therefore very obvious that the British troops would directly push through to Zeeland Flanders and Walcheren. If the British were to advance to Woensdrecht, 25 kilometers north of Antwerp, the entrance to Zeeland for the Germans would have been cut off. Pushing through from Woensdrecht via Zuid-Beveland to Walcheren seemed like a relatively simple matter because the 70th German infantry division had been commissioned to go to Flanders on 1 September. The backward units were certainly not prepared for battle. Immediate continuation of the Allies to the Zeeland islands would have enormous consequences for the 15th German army of Gustav von Zangen, who from France with 100,000 troops was trapped on the Channel Coast and the Flemish coast.

The philosophy of Pip Roberts was that if your opponent showed signs of weakness, you had to exert extra pressure. His armoured division was certainly able to continue the advance on 4 and 5 September. From above, however, Pip Roberts was commissioned to take 2 days of rest, very against the will of Pip Roberts, which lost a great possibility for a rapid Allied occupation of the Scheldemond. At Eisenhower’s headquarters, the plan was suggested to occupy Walcheren using 2 American paratrooper divisions. Montgomery did not care much about these plans and had other plans, as it turned out later. The chance of a rapid conquest of the Scheldt estuary was definitely lost when Montgomery’s XXXth Army Corps was ordered to leave his position near Antwerp and move east.

It gave Von Zangen and the 15th Army the opportunity to retreat to Breskens and eventually make the crossing over the Westerschelde and retreat behind the Festung Schelde Süd. The British commanders were aware of this but did not take the evacuation seriously at first. It was not until September 9 that it became clear that large quantities of men and vehicles had been transferred. 86,000 troops, 6,222 vehicles, 6,200 horses and 6,500 bicycles were transferred from the Netherlands using the existing ferry services and additional ships. This evacuation led by Hermann Knuth was considered a victory by the Germans and contributed to “Das Wunder in Westen”. There was no ignorance in the Allied high command. The intelligence service was well informed and the resistance of Zeeland had also painted an accurate picture of the German troops present. But Montgomery had other ideas.

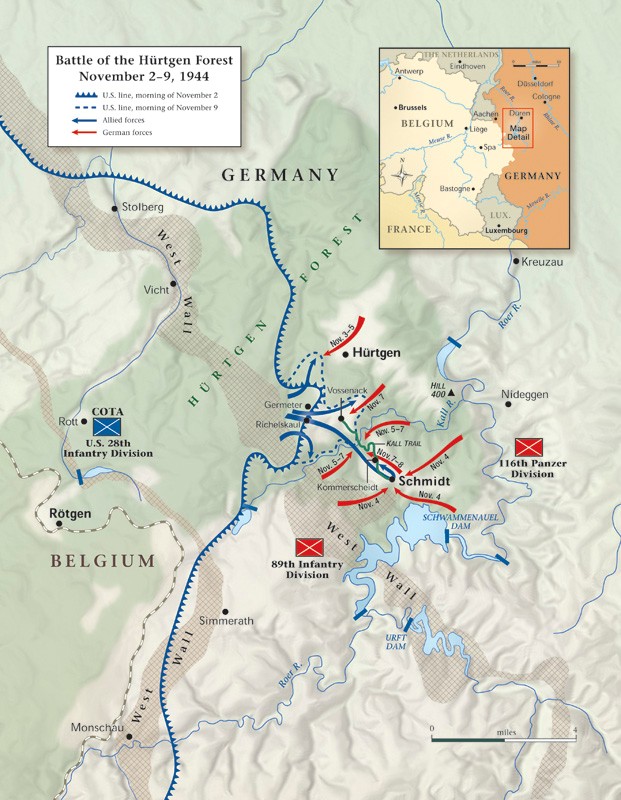

The Battle of the Hürtgenwald

The original purpose of the U.S. commanders was to pin down German troops in the area around Aachen to prevent them from strengthening the front lines further north in the Battle of Aachen, where U.S. troops fought against the Siegfried Line network. A secondary goal may have been to surround the front line. The initial tactical objectives of the Americans were to take Schmidt and clear Monschau. In a second phase, the Allies wanted to advance to the Ruhr River as part of Operation Queen. The area was located in the triangle Aachen, Monschau and Düren.

Why it was decided to pull through the forest will always remain a mystery. Why didn’t they go around it? In the forest one could not use the support of the Air Force, in the open areas of course.

Walter Model planned to bring the Allied advance to a halt. Although he interfered less with the daily movements of units than at the Battle of Arnhem, he was still fully informed of the situation, he slowed down the progress of the Allies, inflicted heavy losses and took full advantage of the Siegfried line fortifications that the Germans had. Model’s ultimate goal was to protect the area behind the Hürtgenwald. After all, Hitler had issued the order to prepare the Battle of the Bulge (Hirbstnebel/Wacht am Rhein). Large quantities of tanks and other moving equipment and large quantities of troops were collected in the area behind the Hürtgenwald. Special measures were taken to ensure that moving tanks make as little noise as possible. Of course, the Allies were not aware of this.

The Hürtgenwald cost the U.S. First Army at least 33,000 dead and wounded with a highest estimate of 55,000. The German casualties estimate was 28,000 dead and wounded. The city of Aachen in the north eventually fell on October 22, but they failed to cross the Ruhr or take control of the Germans’ dams. The battle was so costly that it is described as an Allied defeat of the first order, with specific honor for Model. The historical discussion revolves around whether or not the U.S. battle plan was operational or tactical. An analysis is that the Allies underestimated the strength and determination that were still in the psyche of the German soldier as a result of the defeats in the Normandy landing and outbreak and the subsequent Battle of Falaise. American commanders in particular misunderstood the impassability of the dense Hürtgenwald. The better alternative by breaking the southeast to the open valley, where the benefit of air support would come into its own, does not really appear to have been considered by headquarters.

Len Lomell

A veteran of D-Day, Len Lomell summed up the battle as follows: “June 6 was not my longest day, December 7 was my longest and most miserable day on earth throughout my life. He added: “The months-long battle for the Hürtgenwald was a miss that the highest echelon never wanted to talk about again”.

Norman Cota

For Norman Cota, the battle of the Hürtgenwald became a complete drama. The hero of D-Day on Omaha beach, where he managed to keep the men on his feet under appalling circumstances and eventually managed to reach an exit from the beach, was taken apart after the largely failure of the battle by Courtney Hodges with the accusation that he had done too little to know what exactly had happened and had shown too little effort. However, Hodges’ advice to replace Cota was not implemented.

The battle of the Hürtgenwald was temporarily stopped by the outbreak of the battles at the Battle of the Bulge. All American units were needed in the counter-attack in the Ardennes. The Battle of the Ardennes lasted from 16 December 1944 to 25 January 1945. After January 25, the fighting around the Hürtgenwald continued again.

James Gavin

When on 8 February 1945, the 82nd Airborne Division arrived at the Hürtgenwald, General James Gavin could not believe his eyes. He was amazed at the chaos of barbed wire barriers and the wide variety of all kinds of mines and the enormous amount of bunkers present. Gavin followed the Kall path in a jeep down from Vossenack. When they got stuck on the wrecks, he moved on on foot. In addition to the broken tanks and vehicles, there were dead American boys everywhere. At the bottom of the Kall River, Gavin found portables with deceased soldiers. The bandage post was apparently abandoned in a hurry and the injured had been left behind.

When it started to get dark, Gavin returned to Vossenack “through the deepest reaches of Dantes Inferno“. On February 10, 1945, the Ruhrdam was finally taken. When the balance was taken of the battle of the Hürtgenwald, one-fourth of the deployed American troops were found to have been lost, 33,000 men. The 120,000 deployed GIs of the six divisions and an armored division lost 24,000 to dead, wounded, missing and captured men. Furthermore, another 9000 had been removed by illness and exhaustion. The Germans had deployed six divisions, including an Armoured Division, for the defence of the Hürtgenwald, totaling 80,000 men. Four divisions were totally destroyed and the other two had to collect heavy losses. 28,000 Germans fell victim to the fighting including 12,000 dead. The rest were injured or missing or captured.

What had all these destroyed and hurt lives delivered now? The target, the dams, were only reached and taken in February 1945, after the Germans had destroyed the water outlet valves. Entire areas were under water which delayed the continuation of the advance for the 9th Division in particular. Furthermore, 130 square kilometers of useless forest was taken of no tactical value. What had been achieved, the pinning of many precious German troops and material which was subsequently destroyed. These could no longer be used in the Ardennes Offensive and later operations. Len Lomell’s comment above says enough: “The months-long battle for the Hürtgenwald was a miss that the highest echelon never wanted to talk about again”.

The Gustav line

For the execution of phase 4 at the Gustav line, an additional amount of material was supplied and on 11 May 1944 the Allies reopened the fire. Despite fierce opposition, the Allies finally managed to reduce the Germans. The German lines had been breached or passed and that marked the end of the Gustav line. Kesselring ordered Monte Cassino, the remains of the monastery and the surrounding hills to leave and head north. On 18 May, the Poles finally reached the monastery after a 5-month siege and raised the flag. Through another strategic blunder from the Allies, thousands of the German elite units were able to escape north and continue the battle there. In his hunger for success to reach Rome as quickly as possible, General Mark Clark forgot to prevent this escape by concluding main road 6 (Strada Statala 6) in a timely manner. But the Allies were in a hurry to arrive in Rome as soon as possible, where they met the same German troops again.

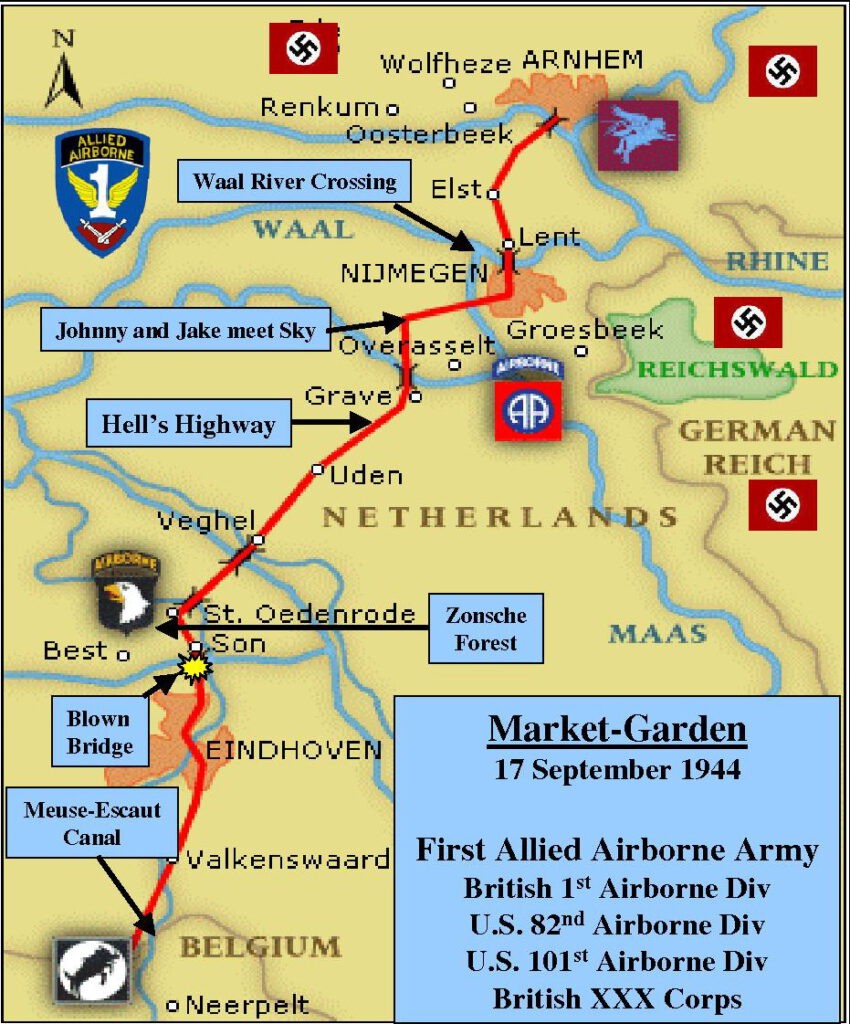

Operation Market – Garden

Although it is always called that the Operation Market – Garden has failed, this is only partially true. Large parts of the Netherlands were liberated, up to and including Nijmegen. Only the ultimate goal, the conquest of the bridge near Arnhem in order to be able to pass through to Germany and end the war before the end of the year (idea Montgomery), was not achieved.

That Montgomery Market-Garden could perform was a direct result of the mutual competition between the American and British troops. The Normandy landings were the idea of the Americans and Montgomery reluctantly joined in. He would have preferred an invasion at Calais, the shortest distance between England and France. And there was the eternal rivalry between the American and English generals, particularly George Patton and Bernard Montgomery. This rivalry was already expressed in the landing and conquest of Sicily. Patton was assigned a certain role, covering the British left flank, while the British would carry out the actual attacking work. Patton was furious about this decision, but was still instructed to abide by his assignment. However, he was given permission to carry out “limited exploration actions” in the east direction. Patton, however, interpreted this permission quite broadly. After this, Patton tried to persuade Lieutenant General Alexander to advance to Palermo. Alexander hesitated, but Patton was already on his way. When Alexander withdrew the consent, Patton was already at the gates of Palermo and Montgomery was well ahead. Patton claimed that the order to stop upon dispatch had become “unclear.”

Montgomery was of the devil. There have been a number of skirmishes between Patton and Montgomery. Because Omar Bradley took a bit more account of Montgomery, at the battle of Falaise, a stop was inserted by Bradley at Montgomery’s request, which maintained a large corridor for the Germans to flee. Patton wanted to continue to shut off the hole completely, but found no hearing with Bradley.

When Montgomery got the idea to perform Operation Market-Garden, all the U.S. generals were against this plan. Also the man from the ranks of Montgomery, appointed to conquer the bridge at Arnhem, Roy Urquhart, calls the mission a “suicide mission”. They preferred to continue on the path taken and conquer more and more ground to the north. Eisenhower was also opposed in the beginning, but Montgomery eventually got his way. Montgomery had barely used his airborne troops and felt it was time to do that. He considered Market-Garden to be a piece of compensation for the Normandy landings, where he should have lost it.

The choice to implement Market-Garden meant a major change in the plans, which meant that the conquest of Walcheren by Pip Roberts could not be carried out. A huge blunder, because making the port of Antwerp usable should have been given the first priority. After all, the necessary supplies were still supplied from Normandy and the port of Antwerp could have significantly reduced the supply time of the stocks. I leave the details of Market-Garden for a moment for what it is, but the number of points that Market-Garden (partly) failed I list here:

Preparation

The preparation time for Market-Garden was one week. Far too little for an operation of this magnitude.

Landing zones

The British landing zones were far too far from Arnhem.

Transport

The Allies had too few planes and gliders to land all the British troops at once. Instead, the landings were smeared out in three days, preventing you from speaking of a surprise attack.

The weather

The bad weather in England and the low-hanging clouds over the drop zones, hindered the transport of the troops and supplies.

Communication

To make matters worse, many of the radios did not work and it was almost impossible to coordinate the attack. The problem with the radios was already clear in England.

Slow progress of the Allied ground forces

Because a giant column of men and vehicles had to take place from Eindhoven to Arnhem on a narrow two-lane road (Hell’s Highway), the advance of the ground troops to relieve the paratroopers in Arnhem took far too long. One hit from a German tank at the front of the column caused another delay because the narrow road was completely blocked.

German armor

It was felt that the German troops around Arnhem were old worn soldiers who were allowed to rest here. The reality was completely different and had already become very clear due to the Dutch resistance and reconnaissance flights. One of the most notorious armoured divisions, led by the German tank ace Willy Bittrich, was present in the landing area of the British Airborne troops. Bittrich was also able to coordinate the defence of the bridge at Arnhem. Frederick “Boy” Browning was aware of the presence of the armor, but he decided that the operations should continue. A risk that ultimately resulted in a disaster for the Allied troops around Arnhem.

Victims

Market-Garden is known as the last triumph of the Wehrmacht in Western Europe. The Allies lost 17,000 troops in more than a week. The Germans lost between 8,000 and 13,000 men in more than a week. Eisenhower considered the result of Market-Garden to be a serious loss and instructed Montgomery to open the port of Antwerp as soon as possible and defeat the German troops on Walcheren, under penalty of relegation if he were to struggle.