Operation Biting and Jubilee.

When the Russians were ready to launch the counterattack in November 1942, Stalin’s desire to open a second front in the west arose. The Germans then had to transfer troops to the west and the Russians then faced weakened German troops. Operation Bagration was about to begin.

The Germans decided to deploy as many German troops as possible against the Russians and to protect the western sea coast with a large number of fixed fortifications (Wiederstandsnesten), which had to be able to withstand an attack from the sea. See here the origin of the Atlantic Wall.

The problem for the English and Americans was the lack of experience for executing an amphibious attack.

To meet the wishes of the Russians, the idea of a large amphibious landing arose in early 1942 to try out the concept of combined operations between land-, sea- and airforces. The Allies wanted to test their tactical theories directly on the ground and see whether the German defense was indeed as good as German propaganda predicted.

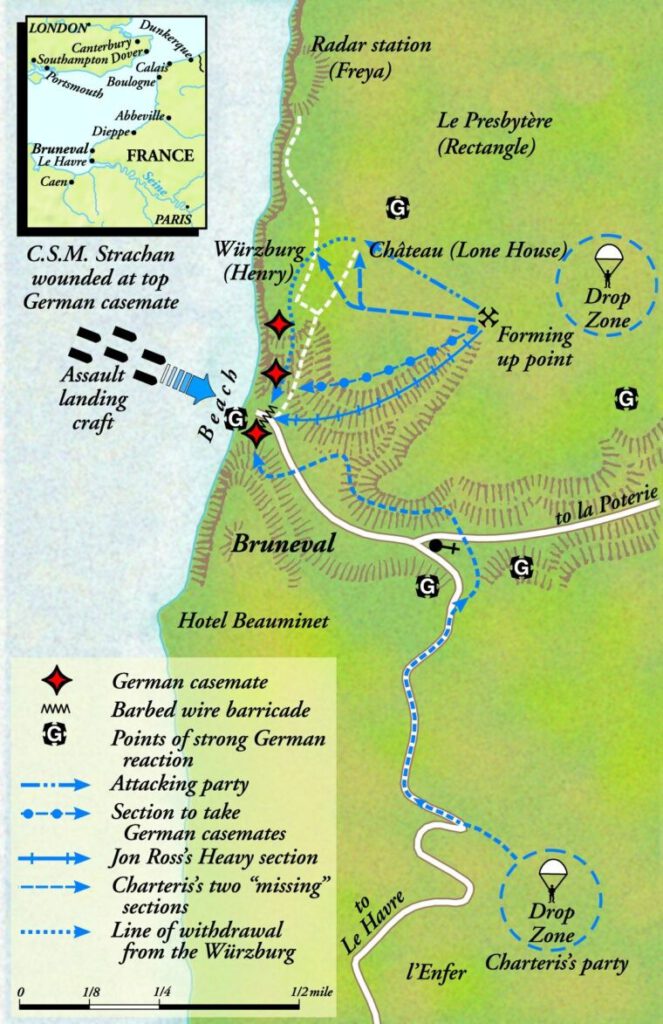

The first attempt was made on 27 February 1942 with the aim of carrying various parts of the German Würzburg radar that was stationed near the town of Bruneval in France. The attack on Bruneval was named Operation Biting and was supported by the Chief joint operations Louis Mountbatten and Winston Churchill.

Operation Biting (the Bruneval Raid)

Units assigned to carry out the attack:

2nd Parachute Bataillon, the Charlie command unit led by John Dutton Frost The command unit was divided into five groups of 40 troops (“Nelson”, “Jellicoe”, “Hardy”, “Drake” and “Rodney”) .

The 51st air squadron for dropping the troops over Bruneval led by Percy Charles Pickard and Nigel Norman.

The Royal Australian Navy led by F.N. Cook, for the evacuation of Frost’s men.

32 troops of the No. 12 Command that would come along to secure the retreat of the men of Frost.

Flight-Sergeant C. Cox, who, as a radio expert, had to dismantle the parts of the Würzburg radar.

Training the mission took place initially at Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire and later at Inveraray in Scotland. Most of the exercises were performed in the dark. Because of the extreme secrecy, the locations were often changed.

The plan

The German unit at Bruneval consists of three parts. The villa “Manoir de la Falaise”, 91 meters from the antenna and the place where the information from the radar station is collected and a number of barracks where 100 soldiers were stationed who are responsible for the defense of the location.

The plan was simple. The paratroopers were dropped into three units. The first unit “Nelson” had to advance and conquer the beach and secure the evacuation route. The second unit “Jellicoe”, “Hardy” and “Drake” had to take the nearby villa and the Würzburg antenna, the third unit “Rodney” had to turn down a possible German counterattack.

The implementation

The paratrooper’s landing did not go completely smoothly (half of the “Nelson”unit missed the dropping zone at 3.2 kilometers), but it took Frost little time to take the villa. Flight-sergeant Cox managed to conquer the Würzburg radar with a number of engineers and take the installation apart and take the parts with them. The Germans had now woken up and attacked the men with heavy artillery and mortars. After half an hour, Frost ordered the withdrawal. That was not easy because a German machine gun’s nest blocked the retreat. The rest of the “Nelson” group who had missed the drop zone, arrived at the right time to silence the machine gun nest, after which the beach could be reached again.

Frost was initially unable to make contact with the landing crafts, but after the setting off of several light bullets, the landing craft suddenly appeared, accompanied by three gunboats. The evacuation was anything but orderly due to the high waves and the constant German gunfire. The men with the precious Würzburg cargo were transferred to the gunboats.

The late arrival of the Navy was caused by a (almost) encounter with a German patrol, a destroyer and two E-boats, which fortunately did not notice them. Upon the light, the ships were protected by a number of NAVY destroyers arriving at the right time and a squadron of Spitfires who further provided the guidance to Portsmouth.

The attack was a huge success. Only two of Frost’s men were killed, six were wounded and six were captured, but survived the war. On the German side six men were killed.

The Attack on Dieppe – Operation Jubilee – The Canadian tragedy

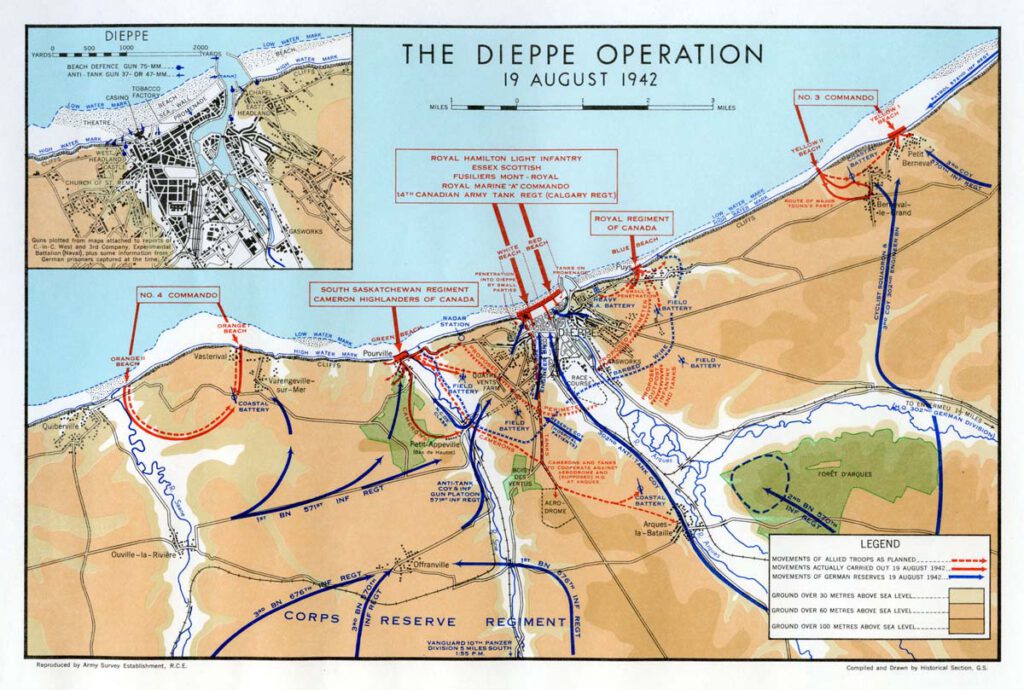

The attack on Dieppe, on August 19, 1942, was a large-scale allied attack on the German occupied port city of Dieppe on the French Channel Coast. It was mainly carried out by Canadian troops and is known as one of the most controversial allied operations from the war.

Why Dieppe?

Following the successful attack on Bruneval, the Allies wanted to gain more experience with combined operations, i.e. operations where the land, air and naval forces had to work together. Amphibious attacks to test German coastal defenses, gather information about radars, ports and coastal defenses, put pressure on Germany and achieve propaganda success. Therefore, a large-scale but temporary attack was planned on Dieppe.

Who was responsible for setting up and carrying out this operation?

Lord Louis Mountbatten – Head of Combined Operations, Major General John Roberts, Commander of Canadian Armed Forces, Captain J. Hughes-Hallet of the Royal Navy and Vice-Marshal T.L. Leigh-Mallory of the RAF/RCAF.

The operation was designed by British planners, but 80% of ground troops were Canadian.

Plan of the Operation

Operation Jubilee was intended as an attack-in-isolation: short, severe, and then retreat. The objectives were as follows: disembarkation at dawn, destruction of the present German artillery, of a radar station, of an airfield, of any warships in the port of Dieppe and the destruction of the German headquarters. Once the missions were completed, the troops had to withdraw as soon as possible and be brought back to England.

On the evening of August 18, 1942, 250 British warships set sail for Dieppe, accompanied by 58 squadrons of aircraft to protect the convoy. 5000 of the 6100 troops were Canadian, the other men English. Five landing sectors were designated near Dieppe:

British 4th Commando on two beaches at Vesterival and Varengeville-sur-Mere to take out German artillery.

South Saskatchewan Regiment together with Cameron Highlanders opposite Pourville, with the mission of neutralizing the reinforced points, advances to the airport and the German headquarters.

Essex Scottish along with the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, the Fusiliers Mont-Royal, the Royal Marine and the Canadian Army’s 14th Cavalry Regiment with the Churchill tanks at Dieppe, with the aim of neutralizing two strongholds at the castle and the casino and taking out the batteries “Bismarck” and “Rommel”.

British 3rd Commando shortly before dawn at Berneval-le-Grand and Petit-Berneval to destroy important German positions.

The plan depended entirely on the element of surprise.

Course of the Raid – August 19, 1942

Early failures

An allied flotilla collided in the dark on a German convoy from Boulogne, losing the surprise. During the fighting, a number of landing craft were destroyed. The Germans were warned and fully alarmed.

Problems on the flank beaches

The troops who had to land on the beaches of Seine-Maritime were welcomed with heavy machine gun fire. The Germans took advantage of the positions that were located on top of the high cliffs and the pebble beach slowed the progress of the artillery and the tanks.

The attack by the British 3rd and 4th Commandos generally went well, although 3rd Commando suffered losses before landing due to action by the Kriegsmarine. The German artillery was eliminated and they achieved their goals as far as possible. At 7.30 the men came under heavy fire again on board with a number of German prisoners.

Opposite Dieppe and Puys, the situation was worrying. Canadian troops remained pinned on the beach, the tanks were stuck in the gravel.

Despite all the problems, General Hamilton ordered the second attack wave to be carried out. His information was flawed, which made him assume that the Canadians were moving into the coastal municipalities. But when the correct information came in about major losses, it was decided to end the attack and return the still-present units. The tanks were left on the beach.

The withdrawal was carried out in complete disorder. The Canadians were almost all eliminated by German crossfire, landing boats were hit by grenades, killing the passengers.

The battles in the air were very intense and the battle was later characterized as one of the biggest aerial battles over the Channel. The RAF/RCAF tried to neutralize the Luftwaffe, but suffered heavy losses. The RAF lost 106 aircraft, the RCAF 13. Controling the air had failed. The naval support was insufficient. The ships were the main target of the Luftwaffe. 34 Allied ships were lost in the attack. The destroyer HMS Berkley was hit by a German bomb and sank.

Losses

The Allies

6,100 men took part, 4,397 were reported missing, imprisoned or injured. Of these, 1197 were killed, including 907 Canadians.

The Germans

Relatively low losses: 600 casualties and hardly any damage to defences.

Causes of failure

No surprise (due to naval battle early in the night), insufficient air and artillery support, the navy did not have enough firepower to destroy German positions, The aircraft did not provide sufficient air support, the tanks could not handle the terrain and the landings were poorly coordinated by poor communication between the units and with the air and naval support.

There was too little realistic information about German defences and the Germans benefited from higher positions and were better prepared.

Consequences and historical significance:

The raid was a military disaster, but the experiences proved crucial for D-Day (Operation Overlord) in June 1944.

Important lessons:

The need for overwhelming artillery support (such as battleships at D-Day)

The development of specialized “Hobart’s Funnies” (see the story “Special inventions during WWII”), tanks to solve various problems on the beaches

The great importance of surprise, deception and logistics

A better choice for a more extensive beach area rather than a narrow harbour.

Winston Churchill later called Dieppe “a costly but essential prelude to success in Normandy.”

From a Canadian perspective:

For Canada, Dieppe is similar to Vimy Ridge in terms of emotional weight – a tragedy that left deep scars. In Operation Jubilee, Canadian troops were disproportionately used as testing forces.

For your information: Vimy Ridge in France, on April 12, 1917 (WWI), the Canadians had made 4000 prisoners of war and retained Vimy Ridge. But at a high price, 3598 Canadians were killed and 7000 were injured. April 9, 1917 is the bloodiest battle in Canadian military history.

Summary:

The Raid on Dieppe was an Allied landing on the French coast, intended to gain experience, test the German defense and put pressure on Germany. The operation failed almost entirely by loss of surprise, strong German defense, inadequate support from artillery, air force and unsuitable terrain. Canadian troops in particular suffered heavy losses. Although tactically a disaster, Dieppe yielded important insights that directly contributed to D-Day’s success two years later.

Source:

The Dieppe Raid – Veterans Affairs Canada

D-Day Overlord – Operation Biting

D-Day Overlord – Operation Jubilee

History.net

Various Wikipedia articles

I really like your writing style, good information, appreciate it for posting : D.