Updated 6/05/2025

In my blog of the bombing of Nijmegen, I already discussed the Allied preparations for the bombing and details about its execution. Here, I will get more into detail about bombing in general and how tactics evolved over time, from precision bombing of strategic targets to bombing raids designed to destroy as many cities and their inhabitants as possible.

The Germans

The German bombing of Warsaw on September 25, 1939, was the first major air raid of World War II. On May 14, 1940, the Germans took the initiative to bomb cities like Rotterdam (May 14, 1940) to underscore the Dutch government’s urgent need for immediate surrender. Under the laws of war, this is not considered a terrorist attack. Rotterdam was razed to the ground, but Amsterdam had already been involved in a mistaken bombing on May 11 in an attempt to disable Schiphol Airport. The damage was limited: 7 buildings and 12 homes destroyed, and 44 dead. The Hague had also been targeted on May 10, during an attack on the Alexander Barracks. The result: 66 dead, 150 wounded, and 100 horses killed. Later in the war, in 1944, Eindhoven was targeted, even though the city had already been liberated. 227 people were killed. Middelburg was attacked by both the Germans and the Allies on May 17. In Belgium, the Allies attacked Mortsel on April 5, 1943 and Hasselt on April 8, 1944. The Allied bombing of the Erla factories near Mortsel ( Luftwaffe repair factory ) was the deadliest bombing of World War II in the Benelux region. 936 people were killed, 238 of whom were children.

The Battle of Britain

Because Churchill would not bow to Hitler’s show of power, Hitler decided to develop an offensive plan to conquer England, Operation Sea Lion. Hitler: “Da England, trotz seiner militärischen aussichtslosen Lage, noch keine Anzeigen einer Verständigungsbereitschaft zu erkennen gibt, habe ich mich entschlossen eine Landungsoperation gegen England vorzubereiten und, wenn nötig durchzuführen.” The German armed forces were strongly opposed to this plan. Germany had no experience with a seaborne invasion force, and the Luftwaffe could only offer limited support. Hitler was not really interested in a seaborne invasion and saw an air campaign as a better means of bringing England to its knees. Moreover, the success of the seaborne invasion required the collapse of the British Air Force (RAF). The most powerful part of the Luftwaffe was its bomber fleet, over 2,000 aircraft, the largest in the world. During the battles in the Netherlands and Belgium, 30% of the fleet had already been lost. The bombers were slow and lacked effective defense. The Messerschmitt Bf 109 was an excellent interceptor to escort the bombers, but lacked the necessary range. The Bf 110, a specialized twin-engine escort fighter, proved unable to hold its own in aerial combat. From August 12th, the Luftwaffe began attacking radar stations and airfields in southern England. Both the German and British air forces suffered enormous losses, and a lack of pilots brought the RAF to the brink of collapse.

On August 25, 1940, the RAF carried out a bombing raid on Berlin. The damage was limited. Göring, who had assured the German people that no bomb would fall on Germany, was called to account by Hitler. The British had to be punished for their brutality. Hitler: “So now, as you know, the British come at night and drop bombs indiscriminately on residential areas, farms, and villages. I didn’t reply immediately, convinced that they would stop this mischief. You understand that we will now reply night after night. If the RAF drops 4 tons on us, we will drop 400 tons on England.” (Hitler could not have imagined at the time that the reality would be exactly the opposite.) The tactics were changed. Airfields were no longer the primary target; instead, cities were attacked. The British now had the opportunity to renovate the airfields and train pilots. From September 7th, large numbers of bombers began attacking major cities such as London (London Blitz), Liverpool, Manchester, Coventry, Plymouth, and Portsmouth. The intention was to crush the British and make them sue for peace. However, the British re-established their RAF, which inflicted increasing losses on the Germans. Ultimately, Hitler and Göring were forced to postpone Operation Sealion indefinitely. The Luftwaffe attempted an alternative strategy, using incendiary bombs, but British morale remained high. London continued to be bombed for weeks, but Hitler ultimately shifted his focus to Russia.

The massive blow the RAF dealt the Luftwaffe was of enormous significance for the rest of the war. Germany never really recovered from the loss of so many aircraft and pilots, and it effectively marked the very beginning of the Third Reich’s downfall.

From September 1940 to May 1941, London, Belfast, Brighton, Bristol, Cardiff, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sunderland, Swansea, and Coventry were bombed repeatedly. London was bombed for 57 consecutive nights. In September 1944, Hitler used his Vergeltungswaffen (V1 and V2 rockets) to bomb London, Glasgow, Manchester and Nottingham.

During the eight months of bombing, 40,000 British civilians were killed and 139,000 wounded. A tactical bombing raid on Coventry on November 14, 1940, resulted in the deaths of 568 British soldiers and the serious injuries of 863. Göring lost 2,000 aircraft and 3,300 pilots and crews and lost his air superiority.

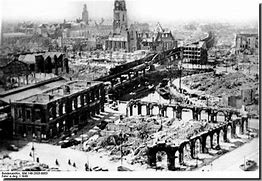

The bombings during Operation Barbarossa

The Luftwaffe also wreaked havoc during Operation Barbarossa. During Operation Störfang in June 1942, countless towns and villages were razed to the ground. The Luftwaffe flew over 23,000 combatflights and dropped 20,000 tons of bombs in June alone. The Wehrmacht went even further, firing 50,000 tons of shells during Störfang. At the end of the siege of Sevastopol, only eleven undamaged buildings remained standing. Leningrad, Smolensk, and especially Stalingrad, along with the surrounding towns and villages, were completely reduced to ruins by the Germans.

The Allies

The Air Marshall of the British Bomber Command was Richard Peirse. Peirse had essentially no strategy. Initially, the target of the night bombings was the oil producing industry in Germany, then the switch was made to the aircraft industry, then back to the oil producing industry, and finally, the German railway network became a priority. The massive bombing of Coventry by the Germans resulted in another strategic shift. In retaliation, the aim was to inflict as much damage as possible on Germany’s major cities. After that, the priority shifted back to the oil producing industry, then to the German navy, and finally to everything at once: railways, industry, and public morale. All in all, these were ineffective actions.

Churchill, June 3, 1942:

“German cities will be subjected to a divine judgment such as no country has ever experienced in terms of sustained duration, severity and magnitude”

And on September 21, 1943:

“To achieve the eradication of Nazi tyranny there is no limit to the violence we will use”

The Americans and the British were the first to develop the concept of a strategic fleet of four-engine bombers. Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, Commander of the Eighth Air Force, got along very well with Arthur “Bomber” Harris of British Bomber Command. However, they initially adopted different strategies. The Americans favored daytime bombing raids, escorted by fighters, while the British preferred nighttime bombing. An added advantage was that this allowed them to take over each other’s day and night shifts. The goal was to bring the war to the heart of the enemy and thus undermine its capacity to wage war. The bombing campaign began with strategic bombing of targets where war materiel was being produced. Efforts were made to avoid residential areas as much as possible and to minimize casualties. The occasional “mistaken” bombing was notable. The list of bombed German cities is endless: Augsburg, Berlin, Braunschweig, Bremen, Darmstadt, Duisburg, Düsseldorf, Essen, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Kassel, Kaiserslautern, Cologne, Leipzig, Munich, Nuremberg, Pforzheim, Saarbrücken, Schweinfurt, Stuttgart, Ulm, Wesel, Wuppertal, and Würzburg, among many other small and large towns. Königsberg, now Kaliningrad, was bombed by both the RAF and the Soviets. Dutch cities were also bombed. Due to mistakes, such as the bombing of Nijmegen, but also deliberately because a strategic target had been discovered: Eindhoven, Arnhem, The Hague, Coevorden, Den Helder, Deventer, Doetinchem, Ede, Enkhuizen, Enschede, Geleen, Goor, Haarlem, Hengelo, Hilversum, Leiden, Nijmegen, Rotterdam, Venlo, Westkapelle, Wolfheze, Zutphen and several other larger and smaller cities throughout the entire war period.

The Butt Report of August 1941 made it clear that the British bombing campaign had minimal effect. This led to the area bombing directive of February 14, 1942: “The primary objective of operations must be to attack the morale of the enemy civilian population, particularly that of the industrial workers. The target points must be residential areas, not shipyards or aircraft factories. This must be made very clear, if it wasn’t already understood”. That same month, a new Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command , Air Marshall Arthur Harris, was appointed .

Harris: “The Nazis started the war naively assuming they could bomb all other countries and that no one would bomb them. They sowed the wind, and now they’re going to harvest the whirlwind, and beyond”:

“The objective of the Combined Bomber Offensive must be unequivocally stated as the destruction of German cities, the killing of workers, and the disruption of civilized life in Germany. The destruction of homes and lives, the creation of an unprecedented refugee crisis, and the collapse of morale both at home and at the front are accepted and intended goals of our bombing policy. They are not byproducts of bombing factories”.

Thus, the new policy was born. The new Air Marshall had spoken. Engineers were considering how to inflict maximum destruction on German cities. New bombers like the Lancaster and the Halifax, with greater range, faster speeds, and higher altitudes, rolled off the production line in large numbers.

During the night of May 30-31, 1942, Cologne was the first victim of the new strategy. Two days later, Essen received the same treatment.

Hamburg and the firestorm

On July 27, 1943, during a raid on Hamburg, a firestorm was created for the first time, by chance. Conditions over Hamburg were perfect. Flak and night fighters were blinded by a radar-jamming measure known as chaff . Metal strips disrupted the German radar image. This prevented the anti-aircraft gunfire, allowing the bombers to approach unhindered. Thanks to the clear weather and the use of H2S radar, the target was accurately located and demarcated, and wind speed and strength had already been relayed to the bombers by Mosquito pathfinders. The bombs fell concentrated in place and time at the intended location. The fire department was hampered by the effects of the cookie mines and the high-explosive bombs with delayed fuses. From July 24 to 30, the city was attacked by the RAF and the USAAF. The tactic was to first blow off the roofs of the houses and then let the incendiary bombs penetrate deep into the houses. The chain of fires thus created a veritable firestorm that destroyed everything at temperatures of around 1,000 degrees Celsius. Hamburg suffered a terrible blow, with 42,000 Germans killed, the highest number of casualties of all bombed German cities, more than in Dresden (although the death toll of 25,000 is far from certain), and more than in all the bombings on England.

Dresden

At the Yalta Conference in early February 1945, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin discussed the future strategy. Stalin requested sabotage of the German army’s supply routes on the Eastern Front. Destroying Dresden was not on the agenda, yet it became one of the main targets of Operation Thunderclap, primarily because of its role as a rail hub for the transport of supplies for the German army to the east. In Dresden, “the Florence on the Elbe,” a city of art and culture, it was long assumed that the Allies wanted to spare the city from air raids. Rumors circulated that the Allies intended to make Dresden the capital of the new Germany. However, the first attack was carried out on October 7, 1944, as an alternative target, and this was repeated on January 17, 1945. Damage to buildings and infrastructure was considerable, but casualties were relatively low.

Bomber Command, meanwhile, had refined its methods, drawing on the knowledge gained from the bombing of Hamburg, to create an effective machine of destruction. On February 13th and 14th, it was Dresden’s turn. The city was barely defended. Luftwaffe fighters were lined up at the local airfield, but the pilots had been explicitly ordered not to take off, as that would have been too much of a drain on the limited fuel supply. The anti-aircraft guns that had surrounded the city had been moved to the Ruhr Valley and the Oder Front. The target was Dresden’s old town, with its many wooden houses. The RAF Pathfinders marked the target with flares at the behest of the Master Bomber . The second wave of RAF bombers released their bombs within the limited space available. First, cookies were dropped—cylinders of 1800, 3600, or 5400 kilograms, consisting of a thin wall and 75% amatol. The blast wave ripped roofs off the houses and crushed windows and doors, transforming them into chimneys. Simultaneously, 227-kilogram high explosive bombs were dropped, aimed at causing total destruction and making streets impassable for firefighting operations. The bombs exploded on the ground inside the houses, damaging gas and water pipes. The damaged water pipes, due to a loss of pressure, resulted in insufficient water for extinguishing the fire. The third wave of RAF bombers dropped their incendiary bombs. The goal was for the smaller fires to merge into larger ones and eventually form a firestorm. The first wave had passed, and the fire brigade, with the help of firefighters from surrounding towns, tried to extinguish the fire. Residents emerged from their air raid shelters, and emergency services attempted to rescue the survivors.

Three hours later, a much larger group of RAF bombers arrived for the main attack. The goal was to hit the emergency services and send them back to cover. Every resident of Dresden heard the deafening explosions but missed a far more treacherous sound: the clatter of 1800-gram magnesium canisters crashing into their homes. These thermite-filled incendiary bombs were the real killers, causing more than five times as much damage and deaths as conventional iron bombs. Terrified, citizens returned to their air raid shelters. The burning city was visible from a great distance, and the goal was to deliberately create a firestorm. The storm could not be extinguished and killed the citizens in the cellars of their homes, or what remained of them. The coal supplies were in the cellars and began to release carbon monoxide. Oxygen deprivation, as the fire sucked in all the oxygen, both above and below ground, and smoke inhalation took their toll. The fire’s heat rose to 800 to 1000 degrees Celsius, melting glass, asphalt, and metal. The upward movement of the hot air drew in colder air, further intensifying the fire. Wind speeds of up to 240 kilometers per hour were reported, twice hurricane force. Trees snapped, and people were sucked into the fire. The firestorm reached an area of 21 square kilometers and a height of 300 meters, ending only when the flammable material was exhausted. The “job” was completed on February 14th and 15th by two raids carried out by the American Air Force. The centrally located marshalling yard was bombed, with stray bombs also landing on surrounding residential areas where thousands of residents had fled to escape the fire. Within a short time, all of Dresden was engulfed in fire of biblical proportions. The damage, if possible, would have been even greater if all the American aircraft had reached their destination. Three groups lost their way over central Germany and, believing it was Dresden, bombed the Czechoslovak capital, Prague. Historian Richard Taylor: “First, the British bombed the Altstadt (Old Town), then the Grosser Garten (Great Garden), and finally, the Americans bombed the undamaged parts of the western suburbs. It was as if the enemy had anticipated every move the Dresden population would make, only to slaughter them like cattle in a corral”.

Lothar Metzger

The story of Lothar Metzger, 9 years old during the bombings, told in the late 1990s:

“I lived with my mother, my sisters, aged five and thirteen, and the five-month-old twins. My father was a carpenter, but had been a soldier since 1939, and we received his last letter in August 1944. My mother’s letters were returned with the message: ‘Cannot be found.’

We were in the shelter for a few minutes when we heard a horrific noise: the bombers. Explosions followed incessantly. Our shelter filled with flames and smoke. We had been hit. The lights went out, and I heard the screams of wounded people. Panicked, we fought our way upstairs. My mother and older sister carried a large basket containing the twins. With one hand, I grabbed my younger sister, and with the other, I clung to my mother’s coat. Our street was unrecognizable. Fire, fire everywhere we looked. What remained of our apartment building went up in flames. Vehicles burned out in the street, while their occupants, refugees and horses, screamed in terror. I saw wounded women, children, and elderly people trying to find their way through the rubble and flames. We fled into another cellar, which was filled with wounded and distraught men, women, and children, shouting, crying, and praying. And then suddenly, a second nighttime attack began. Our new shelter was hit, and we fled again, from one cellar to another. So many, so many people ran desperately into the streets. It’s beyond words. Explosion after explosion. It was unimaginable, worse than your darkest nightmare.

So many people were walking around, badly burned. It was becoming increasingly difficult to breathe. It was dark. In a frenzied panic, we tried to escape a bomb shelter. We stepped over the dead and dying. The basement was full of abandoned luggage. Emergency workers rushed to the scene and took suitcases to evacuate the basement more quickly. We had covered the basket containing the twins with a wet cloth, but it was snatched from our mother’s hands. We could do nothing, as we were pushed upstairs by the mass of people. Outside, I saw the street burning, buildings collapsing. I witnessed a tremendous firestorm. Our mother found some wet blankets in a water barrel and wrapped them around us. I saw terrible things: cremated adults shrunk to the size of small children, pieces of arms and legs, whole families killed by the flames, burning people running back and forth, burned-out buses full of dead refugees, corpses of aid workers and soldiers, many of whom I had heard earlier screaming for their children and families, and fire, fire everywhere, while all the time the hot wind of the firestorm drove people back into the burning houses from which they had just escaped.

I can’t forget these terrible details. I can never forget them. We couldn’t find the basket with the twins, and suddenly my older sister was gone too. Mother quickly realized it was hopeless. We ended up in the basement of a hospital, where we spent our last hours of the night, surrounded by screaming and dying people. At dawn, we left the hospital and searched for the babies and our sister. Only a smoldering pile of rubble remained of our house. We weren’t allowed to enter the house where we’d lost the basket with the twins. Soldiers said everyone inside had been consumed by the flames. Completely exhausted, our hair burned off and covered in severe burns, we walked towards the Loschwitz Bridge, where kind people helped us. We were able to wash, eat, and sleep. But it wasn’t long before a third bombardment began. The house where we’d been sheltered was hit. Once again, we fled into the flames. In this bombing on the afternoon of February 14th, we lost everything we had left, even our identity documents burned. We lost everything. We ran across the bridge with thousands of others and were finally safe. My older sister and the little twins were never found.

Because of all this tragedy, I completely forgot about my tenth birthday. But the next day, my mother surprised me with a piece of sausage she’d begged for from the Red Cross. That was my birthday present”.

Similar stories could have been told by an English or Dutch boy. However, the scale and deliberate extermination of the population in Hamburg and Dresden were incomparable to other bombings.

In 1939, Dresden had a population of 630,000. By early 1945, the population had increased significantly due to the arrival of refugees from the east fleeing the Red Army. There were also many prisoners of war and forced laborers in the city. No one knew the exact number of inhabitants at the time of the bombing; it was thought to be 1 million. Although original estimates were much higher (250,000 dead), the current estimate is 25,000 casualties during the bombing. 80,000 houses were completely destroyed and 100,000 severely damaged. The entire city center was reduced to rubble.

The military results of the bombing were rather disappointing. None of the bridges over the Elbe were destroyed, and the eighth-largest garrison in the German Reich was not hit at all. Most train stations were also undamaged, meaning that rail connections to the east were operational again within a few days.

That Dresden remained essentially undamaged until just before the end of the war was primarily due to its location and the fact that little strategic importance was attached to the city. The decision to reduce the city to rubble had two purposes: to shorten the war and to show Stalin what the Allies were capable of. Until the end of the war, the inhabitants of Dresden suffered from hunger, and many more died from various diseases. To prevent epidemics, thousands of the dead were cremated and buried in a mass grave at the Heidefriedhof cemetery.

The Red Army captured the city on the last day of the war, May 8, 1945. For the remaining inhabitants of Dresden, the worst was now over.

Arthur (Bomber) Harris

Arthur Harris was born on 13 April 1892 in Cheltenham. He was educated at All Hallows School in Dorset. At sixteen, he went to Rhodesia and, at the outbreak of the First World War, enlisted in the First Rhodesian Regiment and served in South Africa. In 1915, he returned to England and joined the Royal Flying Corps. He became a flight commander and fought in France. Harris remained in the Royal Air Force after the war and saw service in British India and the Middle East. In 1941, he was appointed Air Marshal and, in February 1942, was given command of Bomber Command.

The Allies had some explaining to do in the neutral press. The devastating results were initially downplayed, and Dresden, like other German cities, was designated a key strategic objective. The city was reportedly packed with tank troops, among other things.

The following text appeared in the British press:

“The relentless, massive bombing of overcrowded German cities is as great a threat to the integrity of the human spirit as anything that has ever happened on this planet. There is no military or political advantage that can justify this blasphemy”.

Churchill wrote to Harris in March 1945:

“It seems to me that the time has come to reconsider whether bombing German cities solely for the purpose of increasing terror is still desirable. Otherwise, we will soon have to govern a completely destroyed country. The destruction of Dresden remains a serious question mark over the execution of Allied bombing raids”.

Harris was extremely pissed-off. Churchill, who had even come up with the idea of bombarding the Germans with mustard gas, suddenly deftly withdrew his hand from “Butcher Harris”.

Harris’s response:

“Without a doubt, we were justified in attacking German cities in the past. Doing so has always been abhorrent. Now that the Germans are almost defeated, we must stop. But attacks on cities, like any other act of war, are unacceptable unless they are strategically justified. They are justified as long as they shorten the war and spare the lives of Allied soldiers. We will only stop the attacks when it is certain they will not have this effect. Personally, I consider all the remains of German cities together not worth the life of a single British grenadier”.

And in his memoirs:

“I know that the destruction of such a large and magnificent city at this late stage of the war can be considered unnecessary, even by a large number of people who concede that previous attacks were fully justified, like any other act during the war. However, the attack on Dresden was considered a military necessity at the time by far more important people than me”.

Harris received the high Russian decoration, the Order of Suvorov . It was clear to the Russians that this type of bombing, like that on Dresden and Hamburg, was slowing down German war production, and that an estimated 10,000 88 mm anti-aircraft guns, including crews and ammunition, remained in Germany and could not be used against the Red Army. This view was confirmed by Albert Speer in 1959. Speer: “Hundreds of thousands of soldiers had to remain at their posts at the guns, often completely inactive for months at a time. No one saw that this was the greatest battle lost for the Germans”. Harris also received the US Army Distinguished Service Medal. In 1946, Harris was appointed a Marshal of the Royal Air Force (the highest rank in the RAF ) and a Member of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath.

British bomber crews had suffered heavy losses. Of a total of 125,000 crew members, 55,573 were killed. But it seems the British preferred to forget the units that did the dirtiest work as quickly as possible. Only in 2012 was an RAF Bomber Command Memorial unveiled, followed by a belated award for former bomber crews. The crews were initially refused a separate medal. Because of this insult to his men, Harris declined to be raised to nobility in 1946. In 1953, when Curchill again became Prime Minister, he was raised to nobility and became a Baronet. Harris lived the rest of his life in Goring-on-Thames and died on April 5, 1984.

International law of war

At the Nuremberg trials, no one was punished for bombing cities. Göring, as leader of the Luftwaffe, was not accused of this. Bombing undefended residential areas was apparently not considered a war crime. General Taylor, chairman of the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal, said: “While it is true that the first heavy bombing of cities was the work of the Germans, it is also true that the ruins of German and Japanese cities were the result of a deliberate strategy. This proves that bombing cities and factories has become a recognized part of modern warfare, practiced by all nations”.

The Nazis initiated the terror bombings, but they were repaid with interest, and the bombings became part of international warfare. The fact that more than 10 German civilians died for every 1 British civilian is merely a detail. A coincidental byproduct of Allied superiority and modern warfare.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Tokyo had been bombed once before, on April 18, 1942. The Doolittle Raid was a response to the cowardly Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and served more to awaken the Japanese that they too were not invulnerable and to boost American morale, than to actually cause serious damage.

That things could be much worse than the actions over English and German cities was proven by the Americans on August 6 and 9, 1945. The Potsdam Conference took place in Berlin from July 17 to August 2. Harry Truman, president after Roosevelt’s death, announced that he had a new and powerful weapon at his disposal. Stalin, already aware of this through espionage, encouraged Truman to do everything he could to end the war. At the conference, the Potsdam Declaration was issued, stipulating that Japan must surrender unconditionally, or face “immediate and utter destruction”. But for the Japanese, unconditional surrender was out of the question because they feared the emperor’s divine position. In response, the B-29 Enola Gay departed for Hiroshima on August 6, carrying the uranium bomb Little Boy . The bomb was dropped at an altitude of 9,500 meters above the city and caused an explosion equivalent to 15 kilotons of TNT. The immediate result was 78,000 victims killed by the enormous blast wave. In the years following the attack, cancer was the leading cause of death. The death toll had already reached 140,000 by the end of 1945, and in 2004, it was concluded that Little Boy claimed a total of 237,062 lives. All this from a single bomb.

Because Japan still resisted unconditional surrender, the B-29 Bockscar took off on August 9th, carrying the plutonium bomb Fat Man. The initial target was Kokura, home to many war industries. However, visibility over Kokura was too poor, and the bomb was diverted to the alternative target of Nagasaki. There, too, visibility was poor, and the bomb was dropped 3 kilometers from the target, over a sparsely populated area. Nevertheless, the attack immediately killed 39,000 and wounded 25,000.

On August 8, the Russians invaded Manchuria despite the non-aggression pact they had signed with Japan. On August 12, Emperor Hirohito decided on Japan’s surrender. The emperor did not speak of surrender, but of acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration. The military leadership still refused to accept the dishonorable surrender and tried to block Hirohito’s speech on August 14. On September 2, the Japanese surrender was officially signed aboard the USS Missouri.

Conclusion

Throughout the war, 2.7 million tons of bombs were dropped. Everywhere, many casualties were suffered. In Germany alone, 1.5 million tons were dropped on German cities, mostly in late 1944 and early 1945. The number of casualties remains a mystery. In England, 25,000, and in Germany, an estimated 410,000. These deaths refer only to the bombings, but countless cities were reduced to ruins by ground bombardments from the Axis and Allies. Add to that the V1 and V2 Vergeltungswaffen attacks on cities like Antwerp, London, and many more, and the human tragedy as a whole becomes incalculable. Moreover, the most beautiful cities, with their renowned architecture and art, were completely destroyed.

It’s tragic that humanity has learned nothing from this. Putin finds it necessary to regularly bombard magnificent cities like Kiev and Odessa with missiles, again with the aim of hitting as many civilians as possible. However, he has learned nothing from the past. Among British citizens, the bombing of London only increased their determination to take on the enemy, exactly the same among German citizens, and in his own country, during the attacks on Stalingrad, the motivation of the Russian population and army ultimately led to the Nazis being pursued and defeated all the way to Berlin.

Source:

Der Bombenkrieg gegen Dresden im Zweiten Weltkrieg – Michael Schmidt

Traces of War – The Bombing of Dresden

Historiek.net – The bombing of Dresden

Masters of the air – Donald L. Miller

1942 Turning Point in the Second World War – Cyril Azouvi – Julien Peltier

Various Wikipedia articles